(This blog was originally published on smalltalk.)

I’m a junior year engineering student and I’ve been working as a Backend Software Engineer Intern at smallcase for the past couple months. This blog is supposed to congregate, go over some of the Software Engineering, optimization, JavaScript and Mongoose related lessons I learned during my internship.

General

Decide a formatting style at the beginning of every project and stick to it.

No matter how small you think a project is going to turn out, decide formatting rules and format code from the start. Even the smallest projects can grow a lot and formatting them later can be a struggle. Pull/Merge requests to an unformatted project are an absolute pain for the reviewer if submission has a formatting commit. Forget about git blame too — it will be rendered useless.

Tip: Use .git-blame-ignore-revs to save git blame from being trashed because of mass-formatting commits.

Optimization

“Premature optimization is the root of all evil”

Okay, maybe not all, but most for sure. Donald Knuth said it in the 60s and it still holds true. Here is the full quote:

We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.

Premature optimization often leads to stealthy bugs and subpar code. Optimization should come later in the development cycle. Focus should always be on writing readable and maintainable code that your co-workers can comprehend. If you’re going to (unnecessarily) sprinkle your code with voodoo magic, do the bare minimum of commenting the explanation or providing a helpful link.

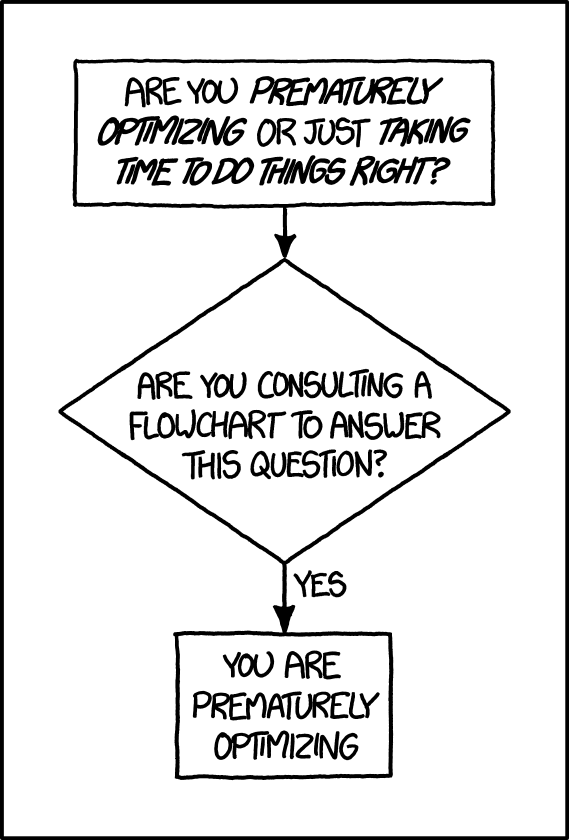

How to know if you’re optimizing prematurely?

XKCD to the rescue! Be sure to go through the explanation.

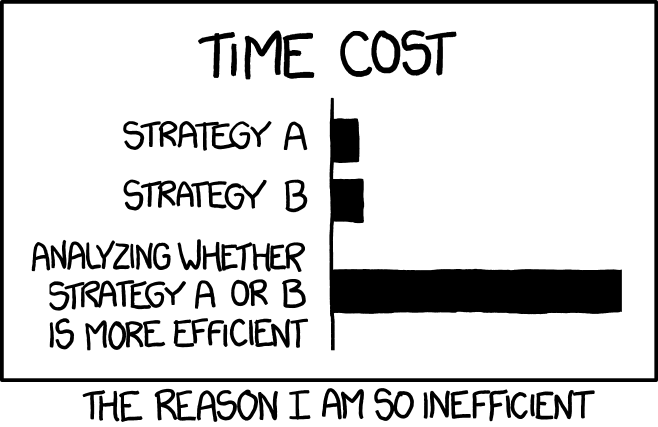

Here’s a bonus XKCD:

Optimization comes at a cost.

Three optimization costs that stick out like a sore thumb are reduction in readability, maintainability of the code and additional bandwidth that needs to be dedicated for the job. The last one is particularly frustrating because even if you do dedicate bandwidth for optimizing a block of code, you’re not guaranteed to get the results. And if you do get the results, they might not be satisfactory if you contrast them with the amount of effort put in. Highly optimized code blocks also tend to be very specialized, harming modularity and reducing reusability.

Keep in mind that optimization is never free. Optimize only if necessary. Give priority to critical sections of the program/system. There’s not much to be gained by optimizing a little job that runs every two hours and processes some simple data. But, a tight loop that gets called after every API call is a great candidate for optimization. Remember — first step of optimization is not how, but if.

Benchmark. Benchmark. Benchmark.

Measure. Don’t assume or guess. Never make non-trivial changes because you think they’ll make the program perform better. Once you are positive that you need to optimize, profiling should be the next step. To optimize, you need to identify the bottlenecks first. To identify the bottlenecks, you need to profile and benchmark first.

Optimizing without benchmarking is blind optimization and should be avoided like the plague. Trying to optimize without profiling will almost always lead to bad optimizations, optimizations which weren’t worth sacrificing the code readability and/or maintainability for, and may sometimes even make the program perform worse. Now you have worse quality code which also runs slower!

Databases are almost always the bottleneck, minimize hitting them.

Any database, in the end, is I/O, and anyone who has dealt with I/O will tell you that I/O is almost always the bottleneck. Try to minimize querying databases as much as you can. If the data you’re querying doesn’t change often, cache it. See if you can get the required result by fetching relevant data and grouping it on your end instead of querying multiple times. But, as always, profile before and after so you can determine whether or not you should let go of the convenience of getting grouped data with a simple query.

JavaScript

Prefer Promises.

What are promises?

Promises are objects that represent the result of an asynchronous operation. Promises were introduced in ECMAScript 2015. As of 2021, all major browsers support Promises and every major library has a Promise API available.

Why Promises?

Async JavaScript or async code, in general, written with callbacks is hard to read. Promise flow, on the other hand, thanks to .then() and chaining, is very easy and intuitive to read. Compare the following code blocks:

function task(){

...

groupData(function(queryResult){

...

groupMore(function(groupedData){

...

processData(function(moreGroupedData){

...

cleanData(function(processedData){

...

sendData(function(cleanedData){

...

});

});

});

});

});

};function task(){

...

.then((queryResult)=>{

...

}).then((groupedData)=>{

...

}).then((moreGroupedData)=>{

...

}).then((processedData)=>{

...

}).then((cleanedData)=>{

...

});

};Promises provide better error handling as well:

function task(){

...

.then((queryResult)=>{

...

}).then((groupedData)=>{

...

}).then((moreGroupedData)=>{

...

}).then((processedData)=>{

...

}).then((cleanedData)=>{

...

}).catch((err)=>{

// Free exception handling without try catch blocks!

});

}What if you wanted to execute a block of code irrespective of whether there was an error?

function task(){

...

.then((queryResult)=>{

...

}).then((groupedData)=>{

...

}).then((moreGroupedData)=>{

...

}).then((processedData)=>{

...

}).then((cleanedData)=>{

...

}).catch((err)=>{

// Handle errors till this point

}).then(()=>{

// Do something

});

}Promises have lots of neat little tricks and features that give them edge over callbacks but listing them is out of the scope of this blog. Refer to MDN — Using Promises for some of them.

Make Promises the first choice when writing async code.

While converting a callback API to a Promise based API is definitely worth the effort, it’s still a fair amount of work. That manpower can be used somewhere else. Most programmers write callback APIs out of old habits and simply because that’s what they’ve been using for a long time. This needs to change. There are very few reasons to use callbacks over Promises, especially in 2021. Promises should be the first choice and not the other way around.

Mongoose

Analyze queries using .explain().

.explain() is a great way to get some solid query execution stats. It dumps a lot of information that you can use to optimize your queries. Try different querying methods, understand querying patterns, see how each of them stack up against each other and make an informed decision. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the output, try shrinking it by reducing verbosity.

Utilize .lean() whenever you can.

From Mongoose documentation:

The lean option tells Mongoose to skip hydrating the result documents. This makes queries faster and less memory intensive, but the result documents are plain old JavaScript objects (POJOs), not Mongoose documents.

Use the .lean() option if you’re querying some data that doesn’t get modified in the process, it can improve querying performance A LOT. A good candidate is a function that only returns a user’s information:

function getData(userName){

...

Users.findOne({ name: userName }).lean()

.then((result)=>{

// return/send the result

})

.catch(...);

};Fetch only required data using projections.

Use projections if you’re dealing with only a subset of fields. Projections always offer much better performance compared to their alternatives. For example — consider that a collection has name, address, phone and age fields, but you’re dealing with only name and address fields. Use

collection.find(query, { name: 1, address: 1 })instead of

collection.find(query).select("name address")